Design doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

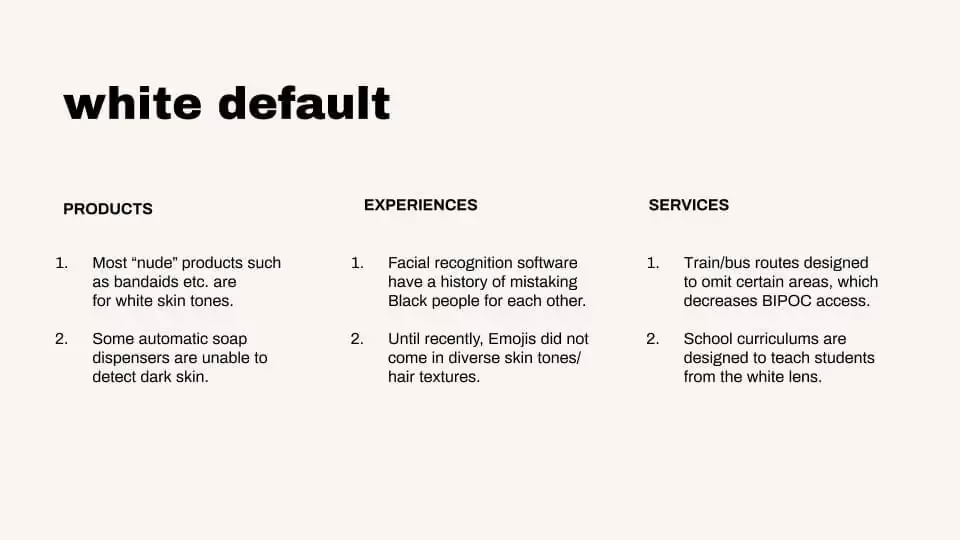

Factors such as race, gender, sexuality, class, age, and ability—and intersections thereof—all impact the way people experience products. Yet these factors are rarely thoroughly examined during the UX research process.

From discovery research, to research design, to research collection, to research analysis—unconscious biases often cause teams to default to white, cisgender, male, and able-bodied users. This leads to products that not only exclude but further harm systematically oppressed communities.

The solution isn’t necessarily more research, but rather more inclusive research.

Inclusive research is the practice of challenging the status quo by intentionally centering diversity, equity and justice throughout the research process. It encourages research teams to think about how different people may experience the solutions we design.

📚 Related Reading: How to Reduce Bias in UX Research

Examples of product failures caused by biased & noninclusive research

In this article, I'll explore the real-world impact of bad research (and let’s be honest, research that excludes large swaths of users is bad research, whether that exclusion is intentional or not) by delving into 6 product failures that could have been prevented with inclusive UX research.

1. Speech-to-text software

Speech-to-text tools recognize spoken words and convert them to text. These tools can help individuals who cannot type due to disabilities such as dyslexia, blindness, hand tremors, or arm injury. They can make a huge difference to the people that need them.

Yet these tools are not equally accessible across racial lines.

In 2020, a team of scientists from Stanford and Georgetown Universities published a study that examined mainstream speech-to-text tools to assess their potential racial disparities. They found that these tools misunderstood—and therefore mistranscribe—Black speakers nearly twice as often as it did white speakers. The average error rate was about 35% for Black speakers and 19% for white speakers.

.avif)

Non-inclusive research obstructs intersectional accessibility. Not only do these tools further exclude Black folks with disabilities who may need them, they also overlook the fact that people have varying accents, ways of pronouncing words and differing native languages.

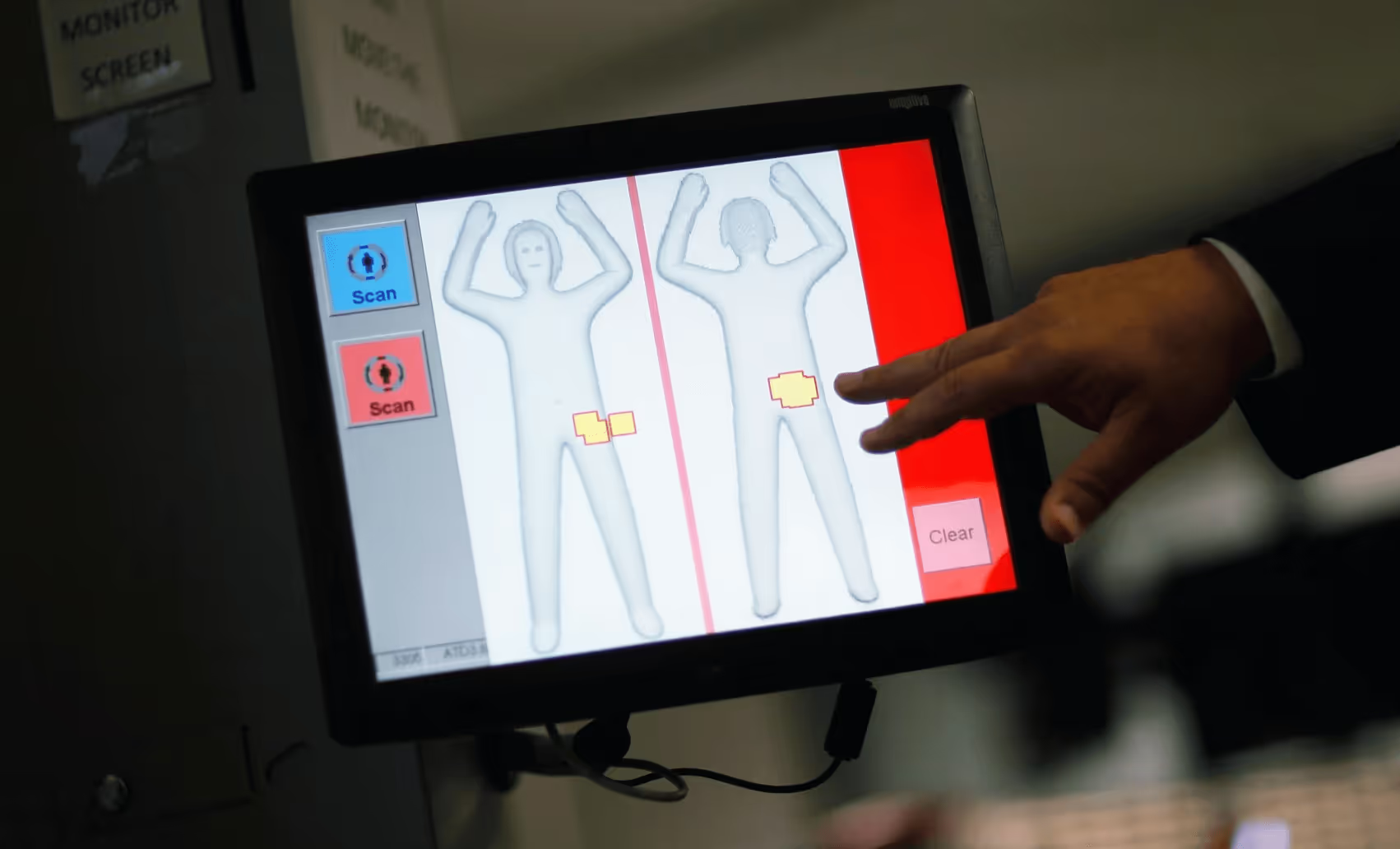

2. Airport body scanners

Airport body scanners are designed to detect masses on individuals' bodies or inside their clothes. However these scanners tend to discriminate, particularly against transgender individuals, Black women, Sikhs, and Muslims.

For one thing, body scanners are programmed to detect private parts based on the male/female gender binary. They make assumptions based on this non-inclusive way of thinking. Thus, if a mass is detected in the groin area of a woman, it is interpreted as a threat. This leads to invasive and traumatizing experiences in which transgender individuals are subjected to pat downs or even asked to show their private parts to security personnel.

Racial discrimination is also common. Many Black women regularly deal with body scans raising false alarms about our hair. Because Black hair tends to be textured and thick, it is not uncommon for those of us with afros, braids, or twists to have our hair searched by TSA agents.

In addition to being triggered by Black hair, these scanners often set off false alarms on individuals who wear cultural and religious head coverings such as turbans and headscarves. This type of discrimination disproportionately impacts Sikhs and Muslims.

3. “Real name” systems

Real name systems require individuals to register an account on a website, blog, or app using their real or legal name. One issue with such systems is that they discriminate against transgender folks, drag queens, and individuals with non-European names. This is because these systems are trained on “real-name” datasets that center on names with European origins.

In September 2014, for example, hundreds of transgender individuals and drag queens had their social media accounts shut down because they weren’t using their given names. In October 2014, an individual named Shane Creepingbear, a member of the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma, tweeted that he was kicked off of Facebook due to claims that he was using a fake name, even though this was not the case.

Many companies have dropped their real name policies after public backlash, but the harm they did—like exposing survivors to their abusers or revealing the names of Vietnamese pro-democracy advocates without their consent—is not so easily undone.

4. Cars and seat belts

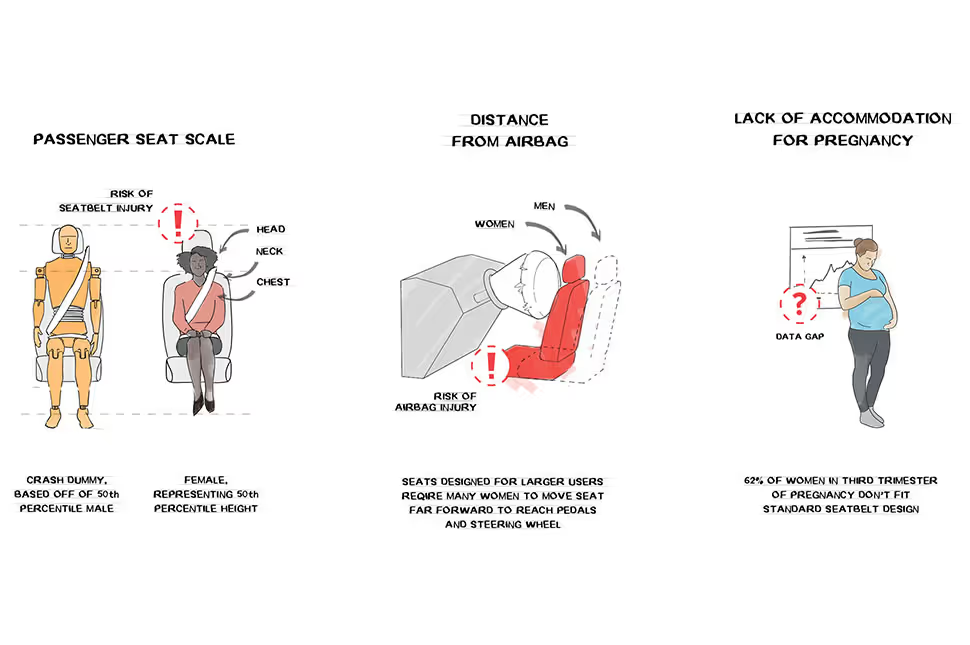

In the 1960’s, car crash test dummies were modeled after the average man in terms of stature, weight and height. Out of the 5 car crash tests used to determine if a car is safe to go on sale; only one of them includes a woman dummy. And this dummy is only placed in the passenger seat. As a result, the design decisions used to improve human safety during car crashes are largely tailored to men.

Many women have to move their seat forward to reach the steering wheels and pedals—which is unsafe. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, individuals who need to sit 10 inches or closer to steering wheels are more likely to experience serious or fatal injuries.

And indeed, data shows that women drivers are 47% more likely to be seriously injured in a car crash.

5. Automatic soap dispensers

Automatic soap dispensers release soap when someone places their hands in front of the sensor—or at least, that’s what they’re supposed to do. In fact, not all automatic soap dispensers can detect individuals with dark skin. In 2015, a video on YouTube showed an automatic soap dispenser which detected light skin, but failed to detect dark skin. As many folks with dark skin can attest, this is not an uncommon experience.

In 2017, Chukwuemeka Afigbo shared a video of another automatic bathroom soap dispenser failing to detect the hand of a dark-skinned individual. When this person placed a white paper towel under the soap dispenser—voila! The soap emerged.

If you’re thinking “that’s annoying but ultimately a mild inconvenience,” let’s remember why automatic soap dispensers exist: to reduce the transmission of disease and contamination by avoiding contact with the bacteria, dirt and germs that people carry on their hands. By failing to detect dark skin tones, this technology is literally putting dark-skinned people at greater risk for disease transmission. In 2021, the implications of that bias at scale should be pretty clear.

6. Algorithmic photo checkers

Algorithmic photo checkers interpret images and are commonly used to verify people’s identities when filling out online applications.

Too often, these tools end up delegitimizing people’s identities instead. In 2016, for example, a Chinese man named Richard Lee was trying to renew his passport online using an algorithmic photo checker operated by the New Zealand Department of Internal Affairs. However, his photo was rejected because the algorithm determined that his eyes were closed. When he tried to upload the photo, he would receive a “subject eyes are closed” error message—even though his eyes were clearly open.

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated incident. In 2010, Time magazine reported that cameras tend to notify people, particularly those of East Asian descent, that their eyes were closed when they were, in fact, open.

Let’s just pause to think about how easily avoidable this situation was—if the research that went into this technology (which is used in products around the globe) had included even a small-but-statistically-significant number of people of East Asian descent in their studies, the algorithm wouldn’t have learned that a Chinese man’s face = error message.

The consequences of bad research design—and how to avoid them

Many of these product failures mirror the dignity assaults that marginalized communities face everyday. It is not uncommon to witness discriminatory insults about Black people’s skin being “too dark”, Asians having narrow eyes, women not being able to drive, Black people not speaking “properly”, transgender folks not being “valid”, Black women’s hair being “inappropriate,” or non-European names being “strange”.

What we are seeing is biases bleeding into our research processes and ultimately informing the products we design. We have the opportunity to disrupt these patterns by implementing inclusive research practices that check our own harmful preconceptions.

Here are some practices teams can implement:

- Require that teams include researchers from a variety of backgrounds.

- Seek out training that examines systematic oppression and how it shows up.

- Practice reflexivity to examine your internalized biases and how these may impact the direction of research.

- Collaborate with research community experts who can help define the problem space.

- Ensure that marginalized communities are involved in planning, facilitating and synthesizing research studies.

- Acknowledge that there are biases in datasets and review/audit them.

- Recruit participants with different identities and backgrounds.

By centering those that have been systematically excluded in our research, we end up designing products, experiences, and services that serve more people and do less harm.