Researchers are not robots, totally free of bias (I mean, even robots aren’t totally free of bias, but you know what I’m saying).

Researchers have values, experiences, desires, expectations, fears, and goals that form their unique and subjective points of view. Acknowledging this subjectivity and the ways in which it can influence your research is a process known as reflexivity.

In this article, we’ll discuss the importance of reflexivity in qualitative research, covering:

- Definition of reflexivity in qualitative research

- Types and examples of reflexivity

- Benefits and potential drawbacks of reflexivity

- Tips for practicing reflexivity as a qualitative researcher

Want to know how researchers can use robots for unmoderated research? Check out our Early Adopter's Guide to AI Moderation for UX Research

What is reflexivity in qualitative research?

.avif)

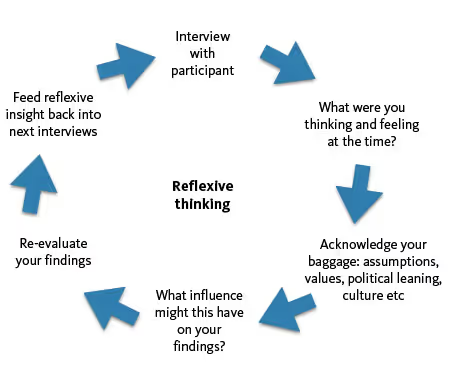

Reflexivity is the process of consciously examining your own subjective point of view as a qualitative researcher and identifying how your subjectivity could impact the outcomes of your research. Basically, reflexivity is the process of asking yourself before, during, and after a study: “Why do I think I know what I think I know?”

A reflexive practice requires you to actively audit and acknowledge:

- Your perspective—the ideals, beliefs, and biases that you carry with you into the study

- Your background, including your education, race, gender, and political/professional affiliations

- Any pre-existing knowledge you had prior to the study, as well as the knowledge you gained over the course of the study

- What, if anything, you have to gain from the study

- The perspectives of your stakeholders and background of the participants you’re recruiting for your research

Here’s an example of the reflexive thinking process from User Experience Consultant Anna Boscoe:

Two key distinctions to know about reflexivity are:

- Reflexivity is not about erasing yourself to achieve “pure and ultimate objectivity.” Instead, it’s about embracing yourself as an active, subjective participant in research in order to deepen your understanding of the findings.

- Reflexivity ≠ reflection. Reflection—thinking carefully about the data and drawing conclusions from it—is a natural part of research. Reflexivity, on the other hand, is about actively questioning your thought process and considering how your perspective shaped the types of conclusions you drew.

Obviously, all researchers—qualitative or quantitative—aim to be as unbiased as possible. But qualitative research is nuanced and descriptive, relying on your own interpretation of the data to generate accurate insights, which makes reflexivity critical.

As Erlinda C. Palaganas et. al. say in their qualitative report:

“As researchers, we need to be cognizant of our contributions to the construction of meanings and of lived experiences throughout the research process.”

Types of reflexivity

The main types or dimensions of reflexivity include:

- Personal reflexivity: This examines your own background as a researcher, including your emotions, assumptions, culture, education, experience, etc., and considers how your background impacts the research.

- Interpersonal reflexivity: This examines your interactions with participants and stakeholders, considering how those interactions shape and are shaped by the research.

- Methodological reflexivity: This examines the research process and design itself; why did you choose to use the methods you used? Why and how did you recruit your participant audience?

- Contextual reflexivity: This examines the social, cultural, and historical context surrounding the study; what assumptions and outcomes might have been heavily influenced by the cultural context in which the study was run?

These different types of reflexivity are not necessarily distinct in the sense that they can be conducted independent of each other; all should be considered as part of an honest, rigorous reflexive process.

This article by University of Melbourne offers some concrete examples of reflexivity in action.

Why should (or shouldn’t) qualitative researchers practice reflexivity?

Your subjective position can impact every aspect of your research, including the questions you choose to explore, the way you design your research, your interactions with participants, the types of data you include or disclude from your analysis, and the conclusions you draw.

It’s important to at least be aware of the ways in which this can affect your approach to making sense of the data—and in some ways, this awareness can help you draw better, more accurate conclusions. As Francisco M. Olmos-Vega et. al. say in their article on reflexivity in qualitative research:

“Embrace your subjectivity; abandon objectivity as a foundational goal and embrace the power of your subjectivity through meaningful reflexivity practices. Reflexivity is not a limitation; it is an asset in your research.”

Types of reflexivity

Reflexivity is typically seen as a beneficial process, because it can help you:

- Identify and reduce bias

- Improve the credibility and trustworthiness of the study (and of yourself as a researcher)

- Improve clarity around decisions

- Aid in your own personal growth

Some of the potential drawbacks with reflexivity include:

- Analysis paralysis

- Time-waste—this is an especially pressing issue in UX or business research

- Narcissism or self-indulgence

- Potential exacerbated issues of privilege—as Francisco M. Olmos-Vega et. al. says: “Newer researchers may worry that admitting confusion and ambiguity could reflect poorly on their credibility and skills as researchers at a time when they are very vulnerable to the assessments of others.”

📚 Related reading: Why a UX Metrics Menu Helps Align Business and Research for Impact (and How to Create Your Own)

How to practice reflexivity as a qualitative researcher

Reflexivity is a great strategy for improving your self-awareness and reducing bias as a researcher. Here are some tips for practicing reflexivity.

1. Start ASAP.

Since reflexivity can affect every aspect of research—from the research questions you choose to explore to the conclusions you draw from the data—it should be a continuous process.

That means that, if you aren’t keeping an ongoing reflexivity journal for yourself throughout your research career, you should at least begin the reflexive process at the start of every study. (See more tips for keeping a reflexive journal in step #4).

2. Practice mindfulness to bolster self-awareness.

Self-awareness is the foundation of an effective reflexive practice—and mindfulness can help you get there.

Mindfulness is an increasingly popular, research-backed strategy for increasing self-awareness, improving self-care, and supporting your overall health and wellbeing as a UX researcher.

By practicing mindfulness, you can improve not only your personal life, but also your ability to remain as objective as possible in your research.

In particular, mindfulness helps you recognize your limits when you’ve hit them. In qualitative research, you’re constantly practicing active listening skills, comprehension, and analysis. If you’re conducting multiple sessions, it’s common to experience empathy fatigue, which can make it more difficult to see yourself clearly for proper reflexive thinking. To avoid empathy fatigue, stay mindful of the number of sessions you’re facilitating and schedule breaks in between sessions to give your brain a rest.

📚 Related reading: The 2023 Self-Care Playbook for UX Researchers

3. Record your assumptions in the research plan.

Listing your baseline assumptions, hypotheses, and anticipated outcomes in your research plan is standard practice.

You can use this list to guide your reflexive thinking throughout the study; revisit it periodically to note how your assumptions and hypotheses may have evolved as your understanding of the topic has deepened.

4. Keep a reflexive journal.

Keep track of your influence on the research process by keeping a journal throughout the study.

For your first entry, you might write an entire narrative autobiography, exploring your background, motives, and specific life experiences that could have an impact on your research.

Throughout and after the study, you might write journal entries exploring questions like:

- How did your personal biases influence the research questions you chose to explore?

- How did your assumptions affect the research design?

- How did your values and beliefs impact your interactions with participants?

- How did your subjectivity affect your analysis?

If you need further inspiration, this article on reflexivity and researcher positionality provides more great examples of reflexive questions.

5. Keep notes during data collection.

You’re almost definitely doing this anyway; note-taking is a critical component of effective research.

So how do you take more reflexive notes throughout the research process? Along with jotting down any facts you’ve observed, you could also make note of any emotional reactions you have to the findings and/or the participants themselves.

These in-session emotional responses can signal key biases or assumptions that you might’ve overlooked. Just make sure to differentiate these types of reflexive notes from your fact-based observational notes to avoid confusion later on.

🧠 More learning: Get tips, templates, and techniques for effective note-taking in UX research

6. Invite other researchers/observers to sessions.

Even if you’re a research team of one, you can still benefit from inviting folks from other teams to act as observers and note-takers during research sessions.

Whether you invite customer success managers, product managers, designers, or executives, each of these teams brings their own unique perspectives and priorities to the session. That means that they’re likely to see details that you miss and provide a more well-rounded understanding of the data. Their input can reveal your own blindspots, aiding in your reflexive process.

Plus, inviting others to tag along with you can help you keep yourself and participants safe during in-person research sessions.

7. Conduct self-interviews, either on yourself or facilitated by another researcher.

Self-interviews can be done using the journaling questions and techniques listed in step #4—but we’d encourage you to invite a colleague to conduct them with you.

The interviewer can help guide you through reflexive questions, illuminating areas you’re skirting around or identifying biases and baseline assumptions that you wouldn’t otherwise notice in yourself.

Ideally, you’d conduct self-interviews multiple times to see if and how your beliefs have changed throughout the course of the study.

8. Ask a “critical friend” to join in and guide your reflexive process.

“Critical friends” are people who can help you explore difficult, reflexive questions and provide alternative perspectives on your research.

If you have the ability to gather multiple critical friends—be they fellow researchers, stakeholders, partners, or people who do research (PwDRs) from other teams—consider conducting a structured reflexive discussion with the entire group.

Francisco M. Olmos-Vega suggests this exercise in an article about practical strategies for reflexivity in qualitative research. First, each member of the group does independent free-writing on a number of reflexive questions, such as these examples from the article:

“In what way might my experience shape my participation in the project?

What experiences have I had with qualitative research?

What is my orientation to qualitative research?

What results do I expect to come out of this project?

What theories do I tend to favor while analyzing data?

What is my stake in the research? What do I hope to get out of it?

What are my fears?”

From there, you can discuss your answers with the group to facilitate the reflexive process as a team.

9. If you’re struggling, use art as a tool for self-discovery.

Reflexivity isn’t easy. As we mentioned before, it requires a deep understanding of yourself and willingness to admit to your own biases, privileges, and predispositions.

If you’re really struggling to engage in the reflexive process fully, genuinely, and honestly, you can try using art to help open yourself up, as Luis R. Alvarez-Hernandez suggests in this article on reflexivity:

“For those new to qualitative research, it may be helpful to engage in reflexivity through creative methods. For example, one can engage in reflexivity using art and creative approaches.”

10. Watch or listen to recordings of your own moderated sessions.

It’s not always easy to remain self-aware during moderated research sessions, and your biases might be apparent in your body language and interactions with the participants.

To identify these moments, Kathryn Haynes suggests watching or listening to recordings of your sessions to study your own behavior:

“Listen to tape recordings, or watch video clips, of your qualitative data gathering (interviews, focus groups, life histories etc) noting how your presence or interaction as the researcher affected the process.”

11. Ask participants to weigh in.

Finally, you can engage in reflexivity by considering the perspectives and input of your participants.

This is a delicate process, as you don’t want participant perspectives to cloud or skew the data. But after the data collection and analysis is complete, you could meet with participants for a follow-up to discuss your findings and allow participants to respond with further insight.

As Francisco M. Olmos-Vega says, collecting this type of feedback can help humanize your participants and help them feel respected and valued for their participation:

“Ethically, these reflexive processes offer participants a say in how their words are interpreted, ensuring that they can represent themselves and contribute meaningfully to research findings. For example, researchers could conduct follow-up interviews to explore how the research has changed participants' views on the study subject or how their practices have been influenced.”

🎙️ Related listening: Doing Participatory UX Research – with Alexis McNutt Unis of Better

Know your role as a UX researcher

Reflexivity is just one strategy in acknowledging and limiting bias in your research.

But great research also depends upon great participants.

That’s why we exist: User Interviews makes it simple to run high-quality research with your target audience. It's the only tool that lets you source, screen, track, and pay participants from your own panel, or from our 3-million-strong network.

Our integrations and API mean we’re compatible with whatever tool stack you’re currently using—and you can get started for free right now.

_1.avif)